In the late-1970s, Michael Hirsh seized an opportunity. An experimental filmmaker whose love of art (and occasional LSD trips) drove him to animation, Hirsh eventually turned his passion into a business, producing independent feature films and shorts that caught the eye of the industry. And one eye would change his life: George Lucas. In 1978, Lucas hired Hirsh and his company Nelvana to produce an animated short for the upcoming Star Wars Holiday Special on CBS. The special may have been legendarily bad, but Hirsh delivered the best part, an animated introduction to Boba Fett, and kicked off an unfathomable career, having produced everything from Inspector Gadget, Beetlejuice (the series), Babar, The Adventures of Tintin, The Care Bears Movie, and The Magic School Bus.

Hirsh would even work with Lucas again a second time, establishing the Saturday Morning Cartoon-ification of Star Wars in the form of two series: Ewoks and Droids. In this exclusive excerpt from Hirsh’s memoir Animation Nation: How We Built a Cartoon Empire, the producer explains the challenging process of working with Lucas at a time when Nelvana needed a financial win, figuring out who Star Wars’ droids would be without Luke Skywalker around, and the bizarre tale of Ewoks’ theme song.

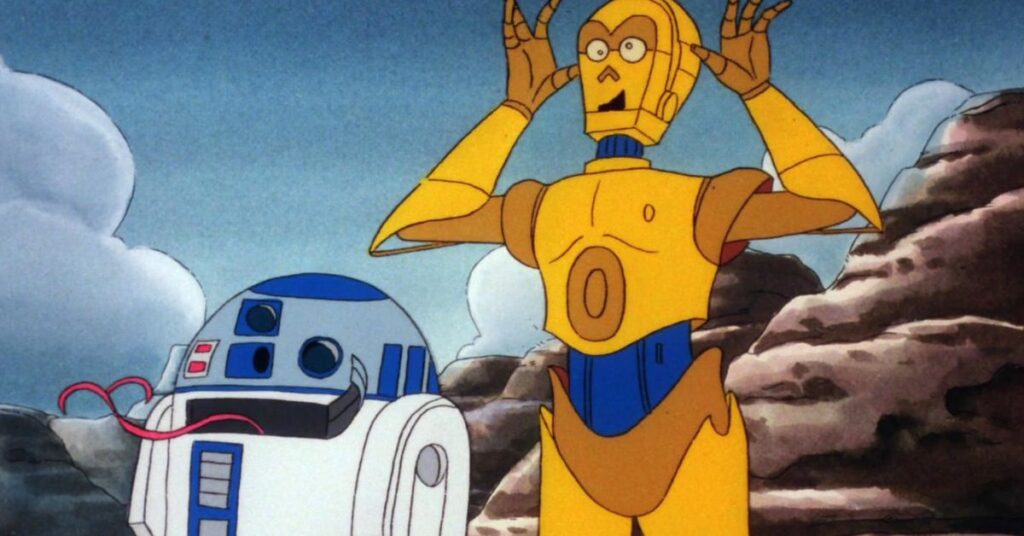

Around this time, I got another surprise call from Lucasfilm telling me that they had sold two animated Star Wars spinoffs to the ABC network: Droids, about the adventures of R2D2 and C3PO, and Ewoks, about the fierce but lovable creatures who lived on the planet Endor. The shows were part of George Lucas’s plan to maintain the merchandising business for Star Wars in the absence of new Star Wars movies. Each series was conceived so that every three or four episodes could be combined into made-for-video movies. I was surprised to find that George didn’t want Darth Vader, Luke, Leia or Hans to appear in the shows, but we did get permission to use some of the Star Wars theme music.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25532016/5029058.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25532017/5028927.jpg)

Image: Lucasfilm

Nelvana produced both shows, making the storyboards and layouts in Toronto and then animating overseas. We did Droids in Korea with Steven Hahn and Ewoks in Taiwan with James Wang. A lot of blood, sweat and tears went into making the shows great, but neither series rated well. Droids only lasted one season and Ewoks two. I think one of the problems we ran into was that Saturday Morning network TV had too many restrictions on violence. We weren’t allowed to show anything that kids might imitate so our weapons looked more like vacuum cleaners or channel changers than Star Wars weapons. While the Ewoks in the movie were cute, they were also warriors and that tension got in the way of making it into a successful kids’ series. The plan to do multi-part episodes also became a challenge because ABC standards & practices forbade children’s shows from ending episodes on cliffhangers. We had to design every episode to be complete in itself. Cable TV, which wasn’t bound by FCC regulations, would be a better home for later Star Wars spinoffs like The Clone Wars.

One of the interesting aspects of both series, but especially Droids, was George’s love of deep background and world-building. He introduced us to the works and theories of Joseph Campbell, whose analysis of mythical heroes and their journeys was a big influence on Star Wars. Ewoks was relatively simple as it was mostly inspired by the world of Endor in Return of the Jedi, but Droids was intended to have new leads every four episodes, with R2D2 and C3PO as the only continuing characters. George also kept changing his mind about whether he wanted it to be more comedic or more action-adventure. The two main droids were the Laurel and Hardy of the Star Wars saga, but sometimes George wanted them to be like Yosemite Sam or other Warner Bros. cartoon stars, and sometimes he wanted them to be Eddie Murphy in Beverly Hills Cop. We never found the right direction for the series.

While Ewoks ran more smoothly, it brought one of the most difficult production problems I’ve ever encountered. George had chosen the singer/songwriter Taj Mahal to write and sing the theme song for the series. The demo he delivered was quite rough. With only a week before air date, I went to Hawaii to attend his recording session for the final version and Taj was nowhere to be found. The engineer directed us to a local hotel lounge where we could recruit some singers who could sweeten the demo track with new vocals. We were recording them when Taj Mahal casually walked into the studio. Fortunately, he liked what we were doing and laid down another take of his lead vocal. Despite all this, ABC never liked the theme song and ordered a completely different song for season two.

While we were working on the Star Wars shows, George introduced me to John Lasseter, head of Lucasfilm’s nascent CGI production arm that would be known as Pixar when it was later sold to Apple. George would have liked to use computer animation for Droids and Ewoks. The technology wasn’t there yet, but John was on the critical path to building it, working on the animation side alongside Ed Catmull, who was more focused on the software and technology side. In those days, this type of computer processing needed big mainframe computers that filled a room. We didn’t begin to take computer animation seriously for about another eight years, but then we started to computerize painting, inbetweening, animation and eventually the whole shebang. The reason we outsourced our inbetweening, painting and shooting to Asia starting with Inspector Gadget was that in North America and Europe, the cost of painting an episode was equal to the cost of animating that episode. By the nineties, computerized paint systems allowed us to repatriate that work and earn Canadian tax credits for doing it in-house.

Don’t feel too bad for Hirsh — after Droids and Ewoks, the producer went on to make The Care Bears Movie, which in 1985, became the most successful non-Disney animated film at that time. And there were many shows ahead of him. For more anecdotes from inside the ’90s cartoon boom, check out Animation Nation: How We Built a Cartoon Empire.